Leptogium fluviatile; Collema fluviatile

River Jelly Lichen

As its English name suggests this is one of the cyanobacteria-containing jelly lichens. In its one to two centimetre long, convex finger-like lobes (looking more like a tiny brown seaweed than a lichen) that fan out at the ends it resembles no Lempholemma species or any other Collema likely to be found on boulders and rocks in rivers or lakes where it is regularly exposed during dry periods. It has mostly been confused in the past with Leptogium plicatile. A vertical section through the thallus of a Collema shows it lacks a cellular cortex and so separates it from Leptogium. If this seems too much of a chore then the following table produced by Vince Giavarini in a report for the EA may help:

| Collema dichotomum | Leptogium plicatile |

|

|

|

|

| C. dichotomum - wet state. Photo: R G Woods | C. dichotomum - dry state. Photo: R G Woods |

Searching for it should ideally be at times of drought when it becomes exposed and as it dries out its lobes turn from green-brown to black. It is possible to search for it by feel under the surface of the water. With experience the firm Pontefract cake liquorice texture (rather than jelly as its name would suggest) readily identifies it. It lacks isidia. Apothecia are produced but are not a readily visible or common feature of this lichen.

All Welsh sites are in rivers. Its habitat requirements seem to be fairly exacting. Gilbert et al (2004) provide a comprehensive description of its habitat in Britain. First of all it likes good light and does not occur in heavily shaded sites. A lack of any regular streamside coppicing may now confine this lichen to the larger rivers. It avoids acidic rivers, though appears to dislike pure limestone as a substrate. In Mid Wales the pH of known sites ranges from a minimum of 6 to a maximum of 8.2 and it favours neutral to slightly basic sandstone as a substrate. It is confined to the larger boulders or extensive areas of bedrock but only where the bed load of gravel etc. can safely bypass its rocks in times of flood. So look for sites with extensive rock platforms but with a deep channel down which the gravel and boulders are funnelled. It tolerates some silt being deposited on the thallus but not total burial.

C. dichotomum habitat on the Afon Irfon. Photo: R G Woods

The zone it occupies is only exposed during low flow conditions so for probably at least three quarters of the year it is submerged. In Wales at least it seems to occupy the niche that is favoured by the alga Lemanea and it often occurs with it. Lemanea grows in the winter as long tresses that in the summer are replaced by a low, pan scrubber-like wiry growth. It may be that the river jelly lichen copes better with exposure than Lemanea so populations of the lichen may become reduced after wet summers with little exposure but do better in the period following a dry summer when the Lemanea is checked. It is absent from streams and rivers with highly acidic water.

There has been much confusion regarding its identity and all records should be confirmed by an expert. A number of records were made as part of river survey contracts to NCC and CCW. Very few of these records have proved to be correct or to have ever been confirmed. It is definitely present in the R. Wye from Erwood to Hay and in the Afon Irfon from Llangammarch Wells to close to its confluence with the Wye. All other records from Wye tributaries should perhaps be discounted at this stage.

It was recorded from the Afon Dee between Corwen and Llangollen as part of a CCW funded macrophyte survey in 2008. This record should perhaps be confirmed by a lichenologist. A similar survey produced a record from the confluence of the Afon Senni with the Usk. Despite there being lots of apparently suitable habitat, a careful search of this area in ideal low flow conditions has failed to relocate it or any species closely resembling it. Searches of the Usk around Llangynidr in apparently ideal habitat have failed to find it.

There is one confirmed record from a tributary, the Grwynne Fawr, below Llanbedr in the Brecon Beacons National Park and a specimen from here is held in NMW, collected in 1954. This river now appears to be too shaded and despite careful searches no material has been relocated.

Records from both the Twyi and Teifi cannot be confirmed, nor can records from the Banwy and searches have failed to locate the species again. Dillenius collected a specimen from an “alpine torrent” in Snowdonia (sometimes also referred to as “a lakelet”) in the 1700’s and Leighton (1879) notes a record “from the River Elwy, about half way from the ford opposite the cave to Pont Newydd, 4 miles from Denbigh”. Snowdonia streams may now be too acidic to support it but rivers in Denbigh would be worth a search.

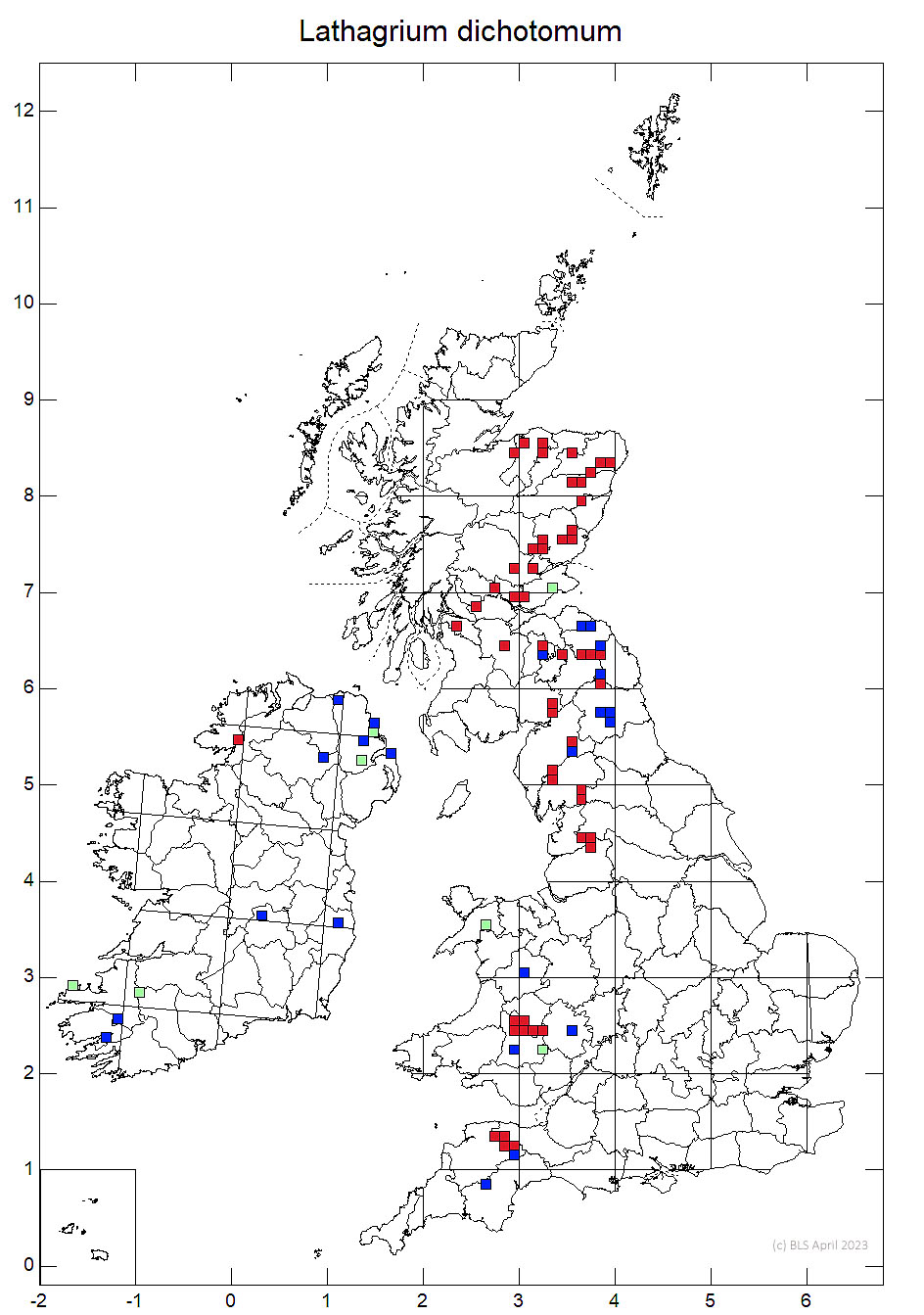

In England it is known from the Rivers Exe and Barle in East Devon and in the North of England from the Rivers Coquet, Eden, Tyne and Tweed. It is also known from Brown Cove Tarn in the Lake District. In Scotland it occurs in a number of rivers in both the Eastern part of the Southern Uplands and in the Eastern Highlands, with new localities recently discovered in Morayshire and North Aberdeenshire.

It is scarce in Ireland with a wide scatter of sites. It is found rarely elsewhere in Europe from France to Fennoscandia and east to Romania.

Maintaining suitable water quality and quantity is clearly important. A monitored population in the River Wye just above Hay has declined markedly. Thick silt deposits encase some of the rocks it formerly occupied, whilst populations on the horizontal top of the rock outcrops have disappeared as the quantities of droppings deposited on these rocks from an ever-growing population of mute swans and Canada geese have increased. The release of compensation water from the Elan Valley dams at times of what would otherwise be very low flow conditions may also limit the area of river bed this lichen can occupy. Acidic atmospheric pollutants may have also rendered some rivers unsuitable. Our more intensive use of the land has also increased the silt load of many rivers to a level that may threaten this species. The growth of trees on riverbanks leading to more intense shade may also limit its spread.

Giavarini, V. J. (2004). Review of the Ecology of Collema dichotomum (River Jelly Lichen) in Britain. Report to the Environment Agency.

- Log in to post comments